Agent of Memory. Interview with Tõnu Tormis and Peeter Linnap

Tōnu Tormis (1954) is an Estonian musician and photographer. From 1981 to 2019, he sang with the Estonian Philharmonic Chamber Choir and performed in various ensembles. In addition to his musical career, he has been active in photography since 1974, even leading a photography club for schoolchildren. In 1981, Tormis became a member of the renowned Estonian photography group STODOM.

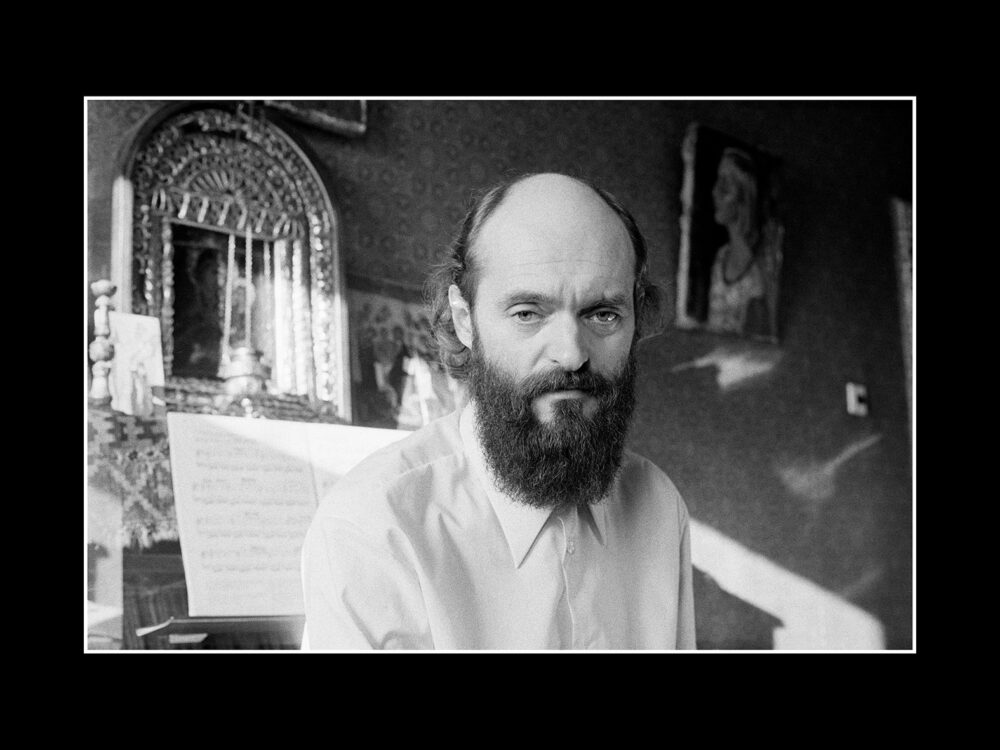

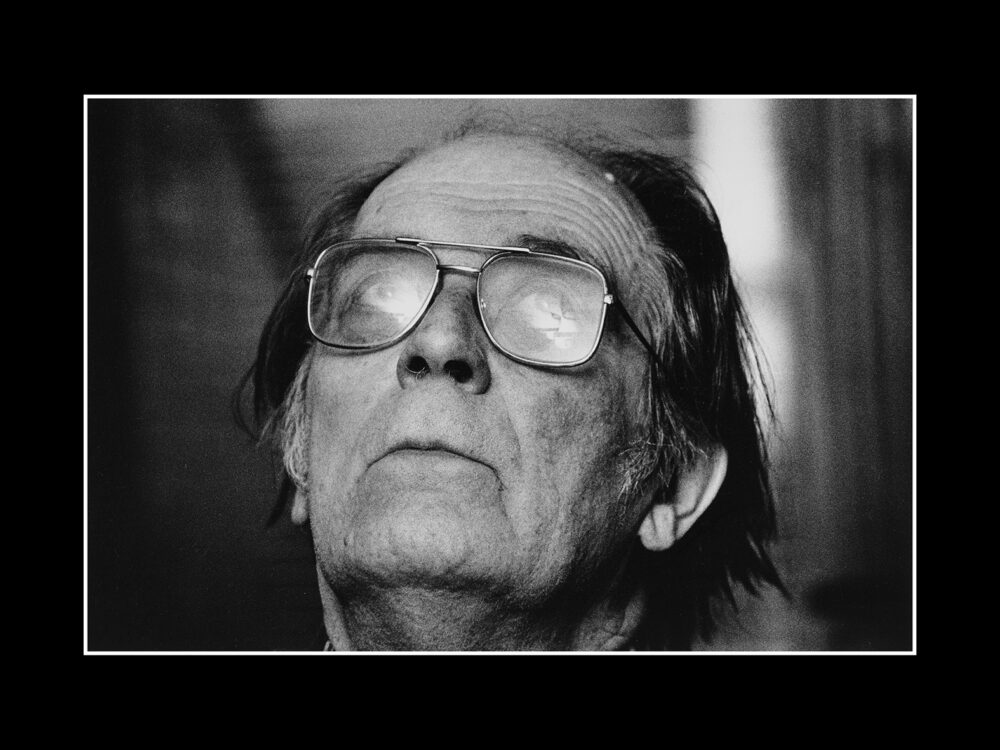

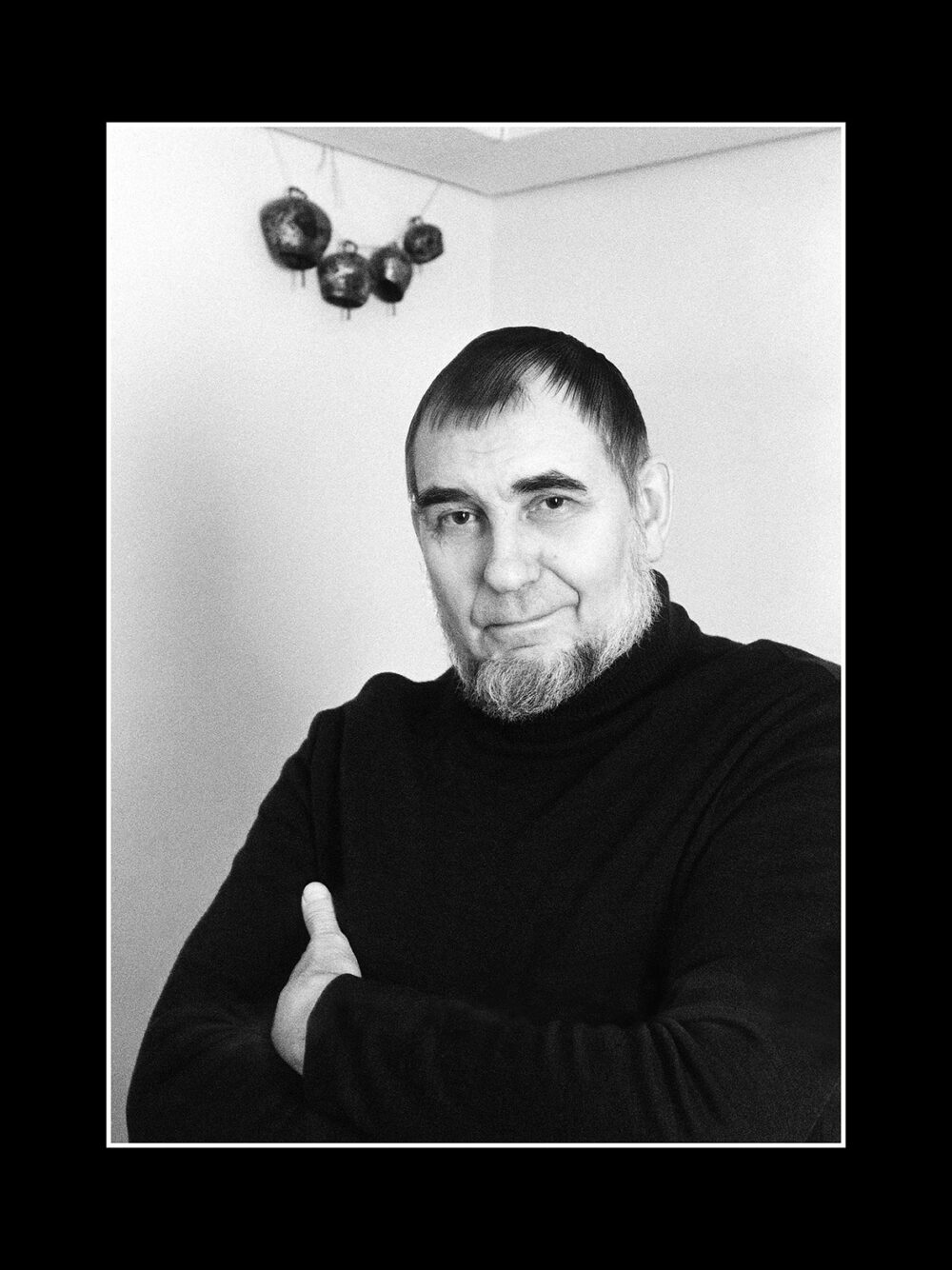

From October 18 to January 18, the University of Tartu Library is hosting an exhibition of portrait photography by Tōnu Tormis, titled Of Time and Mind. The exhibition features 200 portraits of Estonian artists, musicians, writers, and other cultural figures. It is curated by Peeter Linnapp, an art historian, theoretician, and professor at Pallas University in Tartu.

How do you both usually present yourselves to the public?

Tõnu: I had been a tutor at the Pioneers’ Palace for five years when the Ellerhein Chamber Choir, in which I was a singer at the time, became the professional Estonian Philharmonic Chamber Choir in 1981. I changed jobs and became a professional singer with the choir until 2019, when I decided to leave the stage while my abilities were still at their peak. I believe my timing was spot on! Since then, I’ve worked with the EFK, as well as with my father and myself, in the archives. I now refer to myself as an “arch-vaar” (a play on words in Estonian — vaar means an old man or grandfather).

Peeter: Unlike Tõnu, I take on a variety of roles in the cultural field. I am an artist, curator, educator, and theorist. This has its upsides and downsides. On the positive side, it creates diversity in my work; on the negative side, it sometimes makes it harder to focus deeply on any one subject.

Tõnu, can you describe the moment or experience that first drew you to photography? Was there a specific photograph or photographer who inspired you early on?

Early on, there wasn’t any particular photograph or photographer that captured my interest. Instead, I was fascinated by gadgets and machines, as little boys often are. This included my grandmother’s Smena or Ljubitel camera. You could press a button and, later, when the film was developed and the photos printed, you’d see what came out of it.

A few years later, a family friend—an amateur photographer, translator, and editor named Jüri Ojamaa —introduced me to the secrets of the darkroom. This led to some inconvenience for my parents, as the only suitable space for a darkroom in our apartment was the bathroom. Eventually, I was relocated to the basement with all the lab equipment. However, there was no running water there, which is why the photo experiments from that time haven’t been preserved very well.

The current exhibition features portraits of Estonian cultural figures. While Pallas professor Peeter Linnap notes that Estonian photographers have historically focused on capturing the “cultural elite” in their work, this was certainly not a conscious choice for me at first. When my grandfather, the writer Paul Rummo, bought his family a country house on the north coast in 1965 — a year or two after his wife’s tragic death in a car accident — he spent summers there with his children and grandchildren. Occasionally, members of the “cultural elite” would visit him. All I had to do was step into the yard, and they would be there.

I owe thanks to my mother, who advised me not to focus solely on photographing objects, flowers, and other things, but also the people who visited. As a result, my childhood photo archives include snapshots of writers, discoverers, and other cultural figures who have long since passed away. Many of my composer father’s and theatre critic mother’s friends were also frequent visitors to our townhouse, so being around such people felt natural to me rather than the result of any deliberate interest in the “elite.”

As years went by, a deeper interest in photography as a creative and expressive medium began to emerge. My first serious experiments, which I sent to several newspapers and the Theatre and Music Museum’s photo competitions, received positive feedback and won several awards. Recognition is essential for beginner creatives, as it gives them the courage to continue pursuing their chosen field. A significant milestone for me was meeting the artist and photographer Jaan Klõšeiko, who later became a good friend and a mentor in the truest spiritual sense of the word. As the chief artist of the Kunst publishing house, he encouraged me to photograph many artists outside my family’s social circle. Being young at the time and a rather shy communicator — I believe, for many, the camera serves as a kind of hiding place from which to peer into the world while concealing oneself — I viewed these renowned artists, who were at least 10 years my senior, as if they stood on a lofty pedestal.

Now, as I revisited my archives while preparing for this exhibition, I was struck by how warmly and kindly they treated me back then. I found myself falling in love with my subjects all over again—people who, in these photographs, appear much younger than I am now. In 1981, Peeter Tooming invited me to join the legendary photo group STODOM. From there, my photographs began circulating in numerous international exhibitions.

What does portraiture mean to you?

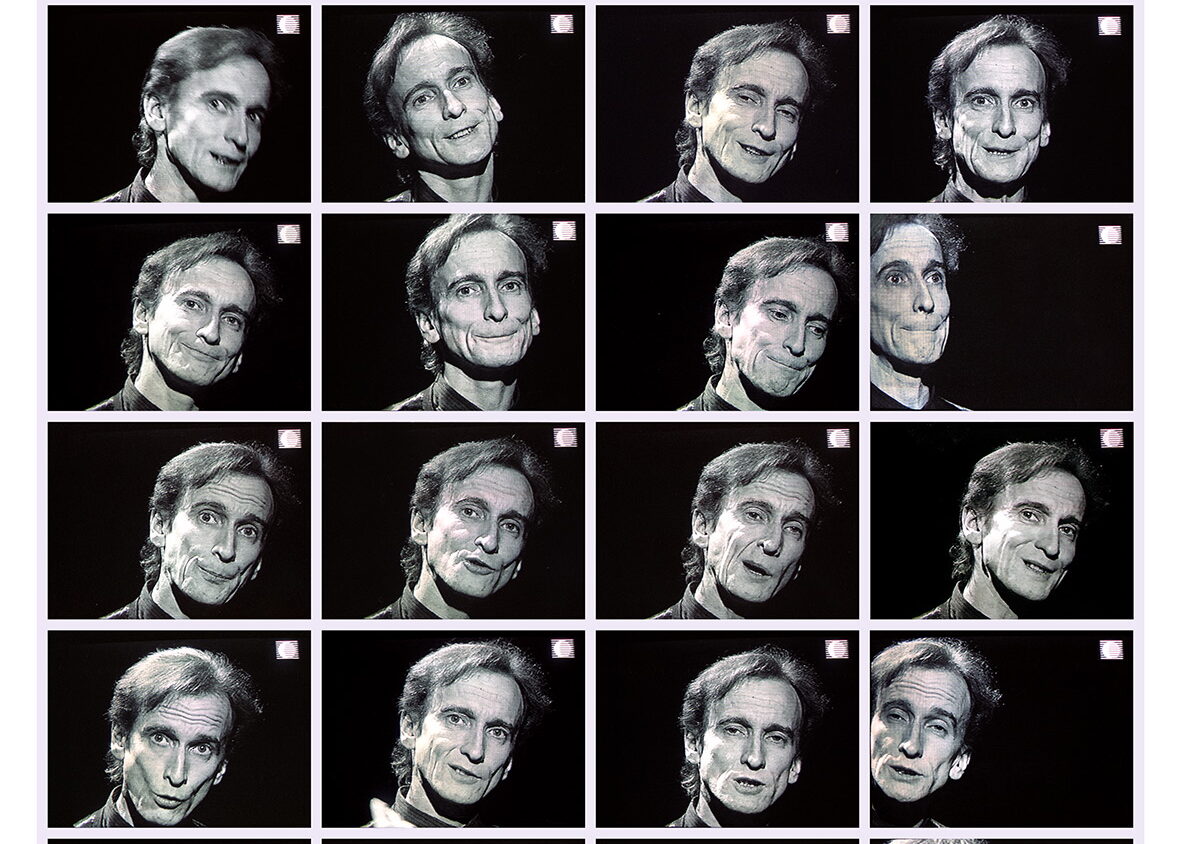

After my initial chance encounters with portraiture as a child, when it later evolved into a conscious creative activity, my greatest challenge became capturing, in some elusive way, the essence of the creative work of the people I portrayed — the quintessence of their personalities in their portraits. Naturally, this was somewhat easier with visual artists and more challenging with individuals from other disciplines.

Is there anything similar about taking pictures and making music?

Absolutely not. In fact, one of these activities has often served as a break from the other—and sometimes even as a form of respite.

Peeter, how did you choose Tõnu’s work to exhibit?

The primary selection was made by Tõnu himself. The exhibition features 200 portraits of cultural figures, and making choices was undoubtedly a challenge for everyone involved. Tõnu has a system that is both chronological and thematic, organized by the profile of the subjects. Chronologically, it begins in 1964, when Tõnu was 10 years old, and ends in 2008, when he turned 54.

That said, Tõnu did ask for my input in cases where there were duplicates or different versions of the same figure. In those moments, I provided a “fresh perspective.” Otherwise, the responsibility for the final selection rests entirely with Tõnu — as an artist, a photographer, and an agent of memory.

How would you describe Tõnu’s work to a reader who is not familiar with Estonian photography? How does he fit into the overall photographic landscape?

Tõnu’s work comes entirely from the black-and-white technological period, where the world of color was “translated” into various shades of grey and black and white. To make this visually simplified and perhaps even more accentuated world more captivating, Tõnu used what is called “punctual light” in his enlarger. A small halogen bulb and a matte black, overpainted enlarger created extremely sharp images that were sometimes somewhere between photography and printmaking. These images were more “flat” than ordinary photographs and, in a way, more sensitive.

In terms of composition, Tõnu aims to create portraits that, when viewed, evoke the essence of the portrayed artist’s own work. For example, if a person in the photograph is a cubist painter, Tõnu’s portrait of him or her will also evoke a cubist aesthetic. This approach likely allows the viewer, even without knowing the person in the picture, to feel a spiritual connection to them. These “inside/outside” aspects of the spirit are certainly expressed more indirectly in the portraits of writers or theatre figures than in those of visual artists.

Do you have any creative plans for the future?

Tõnu: I must admit that after the year it took to prepare and realize this exhibition, my teeth are a little bloody again after a long time, and I’m still thinking about new projects. However, I have to keep my head down because this kind of activity is very energy- and resource-intensive. We shall see.

Peeter: Well, who knows. I’ve published around 25 books, educated nearly 200 students in photography, curated Saaremaa biennials, and created many TV programs… One could easily say that it’s enough now. But no — I have a dream to produce a series of artist books, podcasts, etc., delving deeper. Tõnu’s vast body of photographic work is a part of that plan.