Uglybeautiful. Lars Tunbjörk in Dubulti

More than ten years ago, I came across the book Vinter (Steidl, 2007) by Swedish photographer Lars Tunbjörk. In it, using a direct flash, he captured various everyday banalities during the darkest months of the year. The book was about the loneliness and monotony of winter. At the time, it inspired my aesthetic choice to use flash in the Victory Park project, which was later published as a book (2016). Tunbjörk’s Vinter speaks more to individual experience and solitude, while my Victory Park has a more social focus, highlighting questions of collective memory, identity, and history of Latvia. To some extent, thanks to Tunbjörk, a direct and powerful flash has since become an indispensable tool in my arsenal, helping articulate how I see and feel the world.

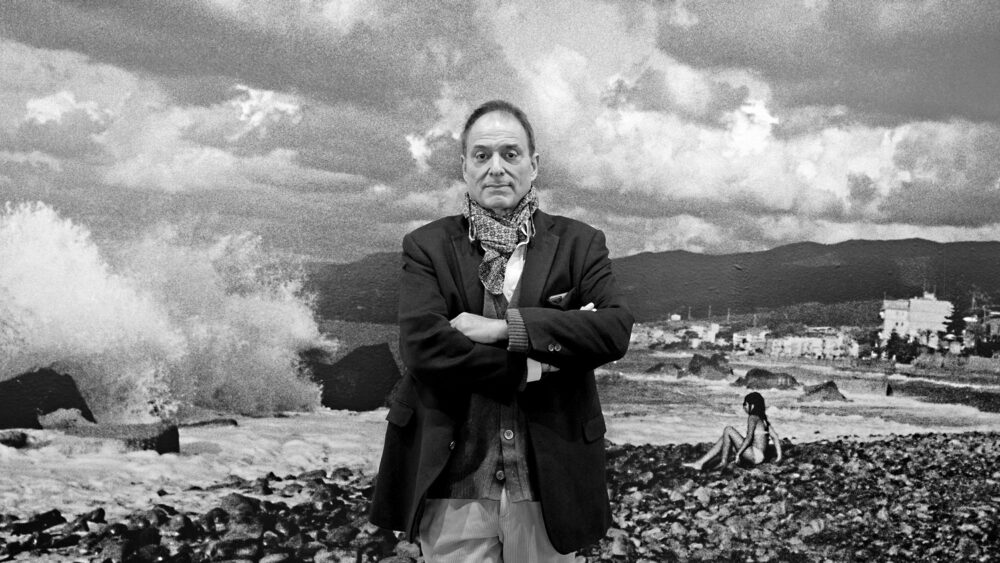

Lars Tunbjörk was born in 1956 in the small Swedish town of Borås, which later became a source of inspiration for him. With its monotonous orderliness and bourgeois daily rituals, Borås symbolised a typical Swedish nowhere. In his works, Borås became a metaphor for the experience of modern Sweden and Western society at large – how people attempt to imbue their lives with meaning and beauty in seemingly unremarkable environments. His photographs, with their vivid colours, precise compositions, and flash-illuminated details, give ordinary scenes deeper significance, revealing and highlighting the absurdity, banality, and poetry of everyday life. Tunbjörk engaged with themes such as alienation, globalisation, and consumer culture, as well as humanity’s attempts to find meaning and enchantment in the mundane. However, Tunbjörk was not a typical Swedish photographer. The Swedish photographic tradition, represented by figures like Christer Strömholm, Anders Petersen, and their countless followers, is rooted in humanism, intimacy, and profound empathy for the people being photographed. That tradition is often characterised by grainy black-and-white imagery. In contrast, Tunbjörk employed colour, humour, and irony, creating a sense of detachment that contrasts with the emotional closeness of his peers’ work. His inspirations and kindred spirits are found in other countries, particularly in American and British photography (Stephen Shore, William Eggleston, and Martin Parr). I often think that my own works also frequently depict people who seem disconnected from their surroundings, from others, or even from themselves. Both Tunbjörk and I focus on landscapes and spaces that reflect the social and economic state of society. These spaces – public (most often) or private (less frequently) – are often empty or stand in stark contrast to their utilitarian function, creating a detached and sometimes absurdly surreal atmosphere. In some ways, Lars and I speak the same visual language.

At the moment, the Art Station Dubulti in Jūrmala is hosting Lars Tunbjörk’s exhibition The Beautiful in the Ugly and the Ugly in the Seemingly Beautiful. While the exhibition features several series, including Office and I Love Borås, its core is centred around photographs taken in the 1990s in the Karosta district of Liepāja in West Latvia. Looking at these images, it becomes clear why the exhibition has such an unusual title. The photographs are simultaneously beautiful and grotesque. They are grotesque because the dilapidated Soviet-era apartment blocks and ruins serve as symbols of degradation and poverty. Yet they are beautiful because the people portrayed are colourful, human, and open. However, more striking than the title is the awareness that, although Karosta has changed, similar images could still be captured in other corners of Latvia. The difference is that I am no longer certain people would so candidly pose amidst the desolation. Sadly, since 2015, Tunbjörk is no longer with us to share his experiences in Latvia, but my own recent encounters in the country’s poorer regions have been varied – ranging from heartfelt kindness to “piss off”. One cannot ignore the fact that times have changed. In today’s world, shaped by social media and digital culture, there is increasing pressure on individuals to keep their image and surroundings perfectly controlled and curated. Photography is no longer just an art form or a documentary medium; it has become a tool for self-expression and image construction, often presenting a reality far removed from the truth. In this context, Tunbjörk’s work takes on even greater significance. It serves as a reminder of photography’s ability to be honest, unfiltered, and deeply human – qualities that are becoming increasingly rare. The interplay of beauty and ugliness is not a flaw but a reflection of life’s true essence. By accepting this contradiction, we gain a deeper awareness of ourselves. Tunbjörk’s works invite us to embrace this acceptance, showing that the world, in all its complexity and disharmony, is exactly as it should be for us to find meaning, beauty, and a clearer understanding of how things could be different.

The exhibition in Dubulti is open until 26 January. The venue is located in a functioning railway station of Dubulti in Jūrmala, the admission is free.